Nothando Lunga

Supervisor

Abstract

Decolonial Praxis and The Question of Land Reform

In KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 1843-Present

In South Africa, the terms independence and freedom are often used interchangeably, although they represent two distinct conditions. Freedom in the postcolony remains inseparable from land, which functions as the material foundation for belonging. And if we are to address the question of belonging as it relates to Africans, we must address the colonial structural entanglement of land with exploitation, toxicity, and violence that continues to shape the present. This study examines how the legacy of forced migration, racialised labour, and land dispossession continues to shape our contemporary spatial realities.

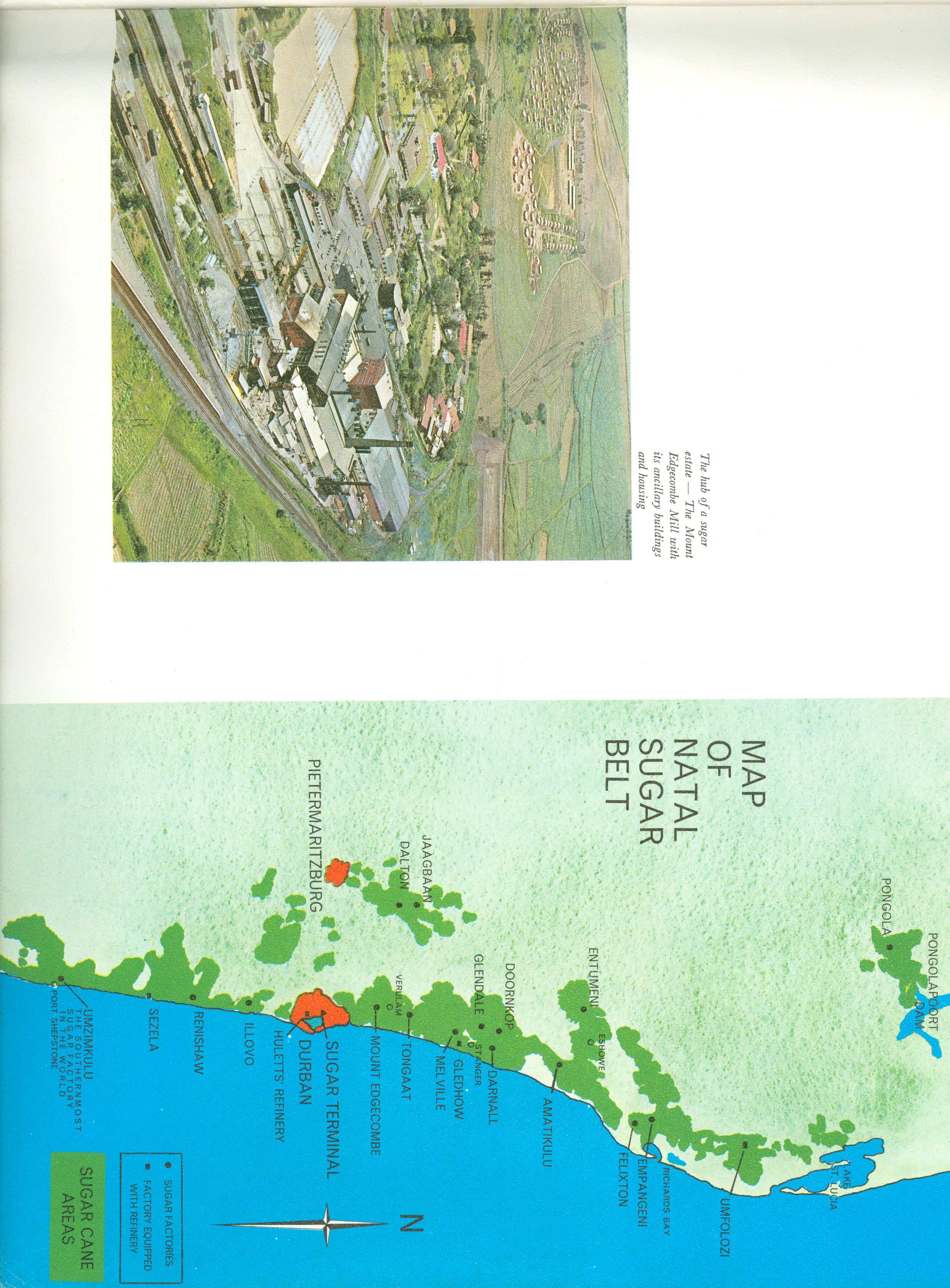

Although colonial ideological borders have been constitutionally de-racialised, their structural endurance remains.Post-colonial settlement patterns reflect and perpetuate these conditions, with post-apartheid developments continuing the logics of segregation and material inequalities. In KwaZulu-Natal, the urban transformation of the colonial NatalSugar Belt into highly secure private estates characterises this continuity.This new form of occupation obstructs meaningful land reform through spatial catastrophes(Sharpe, 2021) that sustain the rhythms of slow violence (Nixon, 2011). Such processes reproduce segregationist geographies that undermine the possibility of transformative decolonial landed freedoms (Allais, 2023). To understand these ongoing effects, we need a critical consideration of this spatialviolence both as a historical foundation and as a contemporary condition.

Central to this study is how architecture, as a lens and practice, can expose this ongoing colonial spatial legacy and contribute to shaping a decolonial future of freedom and belonging in post-apartheid South Africa. This research adopts the method of ‘Radical Witnessing’ (Thomas, 2014) to critically engage with the ‘remains’ (Jucan, Parikka, Schneider, 2018) in postcolonial territories, focusing on restorative justice and the politics of everyday meaning-making(Ndebele, 2026). Within this framework, architecture is used both as a tool for the contemporary interpretation of settlement patterns—revealing the persistence of colonial structural violences — and as a mode of decolonial praxis, one that can materialise transformative realities of belonging.

Bio

Her PhD is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) through the London Arts & Humanities Partnership (LAHP).